Design is on the cusp of a green revolution, which is just as well, because it's time to consider what the world needs.

New life for abandoned railway line

New York’s High Line is a more accessible public space that’s achieved remarkable publicity for its contribution to an urban environment desperately in need of greening: it is a project that reclaimed 22 blocks of abandoned railway snaking through downtown New York and turned it into an elevated urban park and a vital public space. Some 720 teams from 34 countries entered a competition to transform the railway, which was won by landscape architects James Corner Field Operations and architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro. They were joined by renowned Dutch garden designer, Piet Oudolf, who focuses on the structure of plants rather than their colour. The design took the wild growth that existed along the line as inspiration, offering grasslands, sundecks, water features, public spaces, art installations and even performance spaces – creating not only a safe urban park, but also a cultural focal point in New York. The High Line Park has been described as a key example of ‘agri-tecture’ – the fusion of agriculture and architecture.

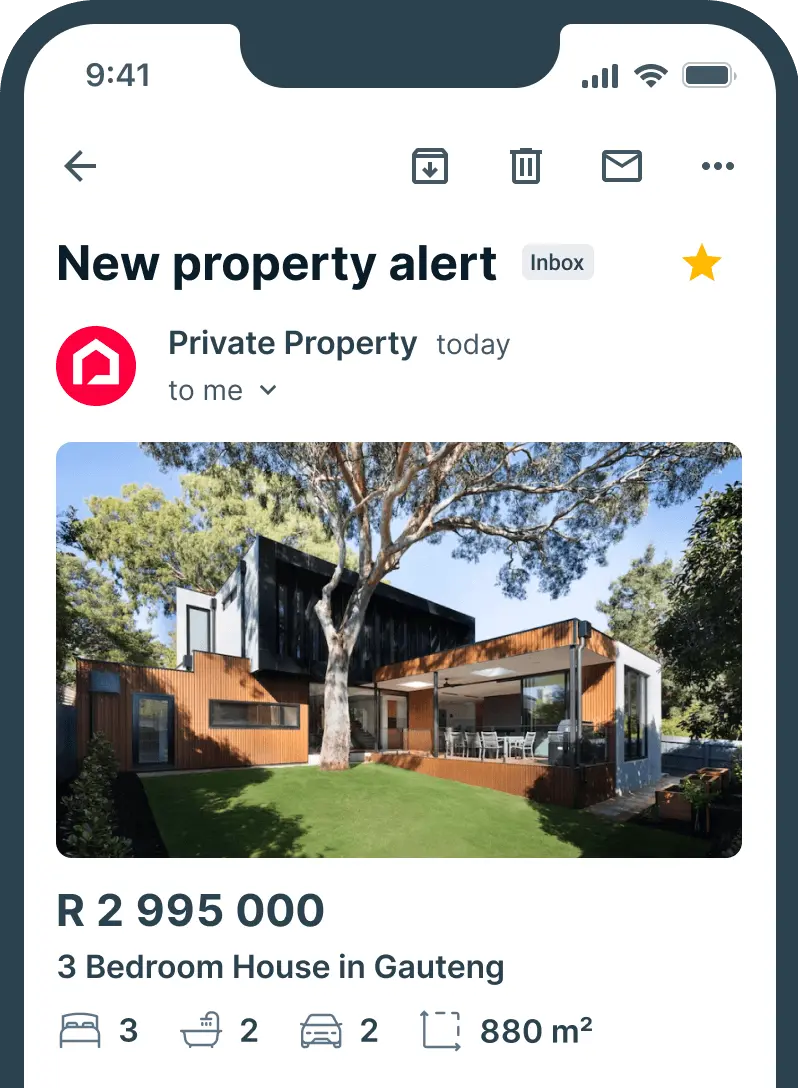

Local hero

What is sustainable design? ‘it’s a notion that’s everywhere but no one seems to know exactly what it means.’ So say the editors of this inspirational project. They invited leading architects, designers, curators, critics, writers and thinkers to ‘nominate superlative projects – objects, buildings and landscapes that are technically or conceptually the best of their kind – in order to create a visual definition of sustainability in design.’The result is an inspiring 350-page book of projects covering product design, architecture, landscape architecture and urban planning, all of which could be influential locally for residential and commercial properties in both urban and rural settings. One thing is certain: ‘the built environment is one of the central players in our environmental crisis and green products can’t exist in isolation from other elements … Architecture should fit within a whole system of sustainability and it should take into account its surroundings, its users and ultimately, its purpose for being.’

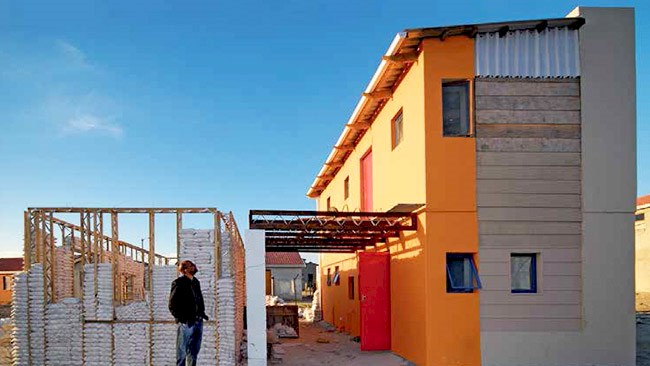

Two local projects included in this book do just that: the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre in Limpopo not only used local materials and employed about 160 labourers from the region, but is also a striking example of creating long-term economic viability in struggling communities. Equally impressive, the Design Indaba 10x10 Low-Cost Housing Project requires no electricity to construct its walls, which are ingeniously insulated with bags of sand filled on site. Design Indaba funded the building of 10 houses in Freedom Park; more are planned for Abu Dhabi (show house completed in June 2010) and Ghana. Each cost just over R74 000 to build at the time. They were built by Luyanda Mpahlwa – who completed his national Architectural Diploma while serving a five-year prison term on Robben Island and later obtained an architectural degree at the Technical university of Berlin, where he spent years in exile. He co-founded MMA Architects, which worked on this project with team leader Kirsty Ronne. He has since established luyanda Mpahlwa DesignSpaceAfrica.

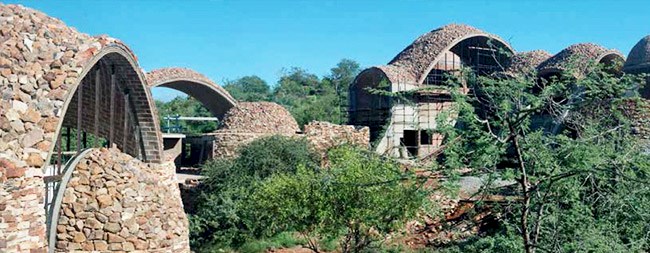

Mapungubwe's self-supporting domes

Peter Rich Architects was responsible for the design of the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, remarkable for its structure: its slender curved and domed roofs are constructed from nothing more than unfired earth tiles overlaid to create roof vaults, a technique that’s been used for centuries. The completed structures are finished with a surface of local stone rubble to subtly set the building into its magnificent natural surroundings. The tiles use 75 percent less energy than reinforced concrete and were made with a hand-press machine that was adapted from local brick-making equipment. Once cast, they take a week to dry but the beauty of this building method is that no steel reinforcement is needed in the structure and so no materials had to be transported from Johannesburg – 10 hours’ drive away.

The earthen tiles are also good insulators: they soak up the heat in the day, while at night, when the temperature drops, they release the heat back into the building. An extra energy-saving benefit of the high vaulted ceilings is that they enable daylight to penetrate deep into the building’s interior, reducing the need for artificial lighting. To create this impressive feat of structural engineering, Peter Rich worked with structural specialists Michael Rummage of Cambridge university and John Ochsendorf of Massachusetts institute of Technology.

Edible front gardens

Edible estates is a project that has turned traditional and wasteful front lawns around the world into vegetable gardens and food sources. Fritz Haeg, a Los Angeles artist, designer and writer, has set out to transform the way we use the groomed patches of grass in our front gardens. He is challenging people to rethink their ornamental lawns, to rip out their water-guzzling, chemical- dusted, mowed turf and replace it with edible fruits, vegetables and herbs. It’s not a new movement – during World War II, Americans were encouraged to grow victory gardens to supplement rations. The movement has spread to London, where affordable housing complexes now have local community gardens growing between them.

Living and breathing

And, finally, one of the most interesting examples in the book is a project by Triptyque, French-Brazilian architects in São Paulo. it’s called Harmonia 57 and is a shop that was originally built as an artist’s studio in a building that breathes, sweats and adjusts itself. Acting like a living organism, it forms a complex ecosystem that treats and reuses rainwater on site, mitigating some of the high temperatures of this tropical climate and utilising Brazil’s heavy rainfall to its advantage. Large, expansive windows and shutters, as well as many terraces, give the building a feeling of openness. The structure is made of organic concrete, which absorbs water via pore-like niches that hold a variety of plant species. As a result, the entire building has a planted façade, irrigated by a misting system. This external vegetal layer acts like an additional skin, buffering the interior against external noise and heat. Harmonia 57 also has a fully integrated, yet technically simple, hydro system of pipes, collectors and tanks, which are integral to the architecture. For example, pipes take the form of handrails, allowing the building’s rainwater and grey water to be reused for the irrigation system and toilets, and to prevent uncontrolled run-off from seeping into the ground. Any surplus of water is collected and stored in three shells located on the ground, which prevent water from flooding the street during periods of intense rainfall. The roof is also planted with greenery, generating fresh air and providing comfortable thermal conditions inside the building, reducing the need for air conditioning. The building’s environmental performance here develops into a new aesthetic: a sophisticated low-tech approach in which the performance becomes integral to the architecture.

Extract from Vitamin Green by Phaidon editors, published by Phaidon (2011) Photographs High line/Iwan Baan; Edible Estates/Jane Sebire, Mapungubwe/Peter Rich; Harmonia/Leonardo Finotti