There was a time in South African suburbs where streets were the places that people wanted to be. These were community performance stages, where children played until the street lights came on and rode to school on bicycles … neighbours gossiped over low-rise walls and shared their concerns and highlights … where walking along avenues of green-laden trees to the local corner cafe or supermarket was common, and (for most) exercise enough.

These are the experiences and memories of the 50-year-plus age group, often referred to as the cross-over generation, for they remember times before technology, before roads became congested, polluted, and became pedestrian hazards. Issues related to traffic, noise, and crime gave rise to gated communities, to isolation and distance from neighbours as people retreated from the streetscapes when urban design widened roads to cater for the growing car population.

What is the current state of affairs?

Now it seems the country has gone somewhat full circle where a new generation of urban designers see streets as places where communities can thrive … albeit not in the suburbs but in the streets of the declining and grubby city centres. They are calling it the Living Street, which Tanya Busschau, a senior Associate at dhk Architects, explains as “design that encourages and facilitates a variety of overlapping systems that have a relationship to one another.

“Living Streets are dynamic public spaces, which are achieved when urban design principles and concepts have been successfully implemented over time to create an environment focused on the pedestrian whilst supporting everyday life in a sustainable way," she says. "To refine the definition is to look at the relationship of many elements working synergistically, such as walkability, shade, planting, scale/proportion of buildings, flexibility of use, etc.

“To create Living Streets requires an understanding of two-dimensional planning aspects and three-dimensional form, as well as the relationship of this form to its surrounding context. Ultimately, it’s about creating a better quality of life.”

Jonny Friedman agrees. He is the Founder and CEO of Urban Lime, a collective of “pioneers’ whose aim is to instigate transformational, valuable and memorable places to live, play and work in. "We strongly understand the nature and psychology of buildings, districts and neighbourhoods in a modern, multi-cultural African city. Through deep engagement and confronting challenges in overlooked areas, we invest and implement a unique approach to each specific area, be that building, context or city.”

Friedman explains that the Living Street concept is still in its infancy in South Africa, but there is some growing recognition of the need for roads that are walkable, bike-friendly, accessible and trendy. This push is being driven dynamically by youth culture, evidence of which we see in densely populated and rundown city centres where the youth adorn barren walls with vibrant graffiti and murals … where cafes and eateries spill onto pavements adorned with vendors’ offerings … and where emerging visual artists’ use low-rental - often rundown - shops as studios. This is not ideal, however, for these are areas that have long been ignored by local governments, and with decline comes crime.

“Crime is the biggest challenge in implementing Living Streets in South Africa, and to make our cities safer, there is a need for local government to provide proper investment, planning and infrastructure design, as well as enforcing regulations that prioritise the safety and accessibility of pedestrians. We need local governments to embrace international best practices where people and the environment are the first priority in our streets.”

To do so is, as Friedman suggests, an economic and social necessity which will see young people gravitate back to a city to live, work, and play. "Living Streets is not purely about pleasant additions. Our cities can play a major role in addressing economic inequality and high youth unemployment, but, I emphasise, only if we create walkable and exciting places. Adding further merit is the aspect of embracing sustainable practices that reduce our dependency on cars and promoting other active forms of transportation, like bicycles.”

Design of the ‘ideal’ Living Street takes into account how the space is used 24 hours a day. It has to "teem with life" and be accessible to individuals of all ages and abilities. It must be a place where all feel comfortable and safe and limits the number of motorised vehicles. Ideally, as is the case in a large number of European cities, motor vehicles are completely banned or traffic calming measures introduced; sidewalks have been widened; fast-moving traffic moved to alternative routes; and dead-end passages opened to access special community centres, parks, plazas, markets and stores.

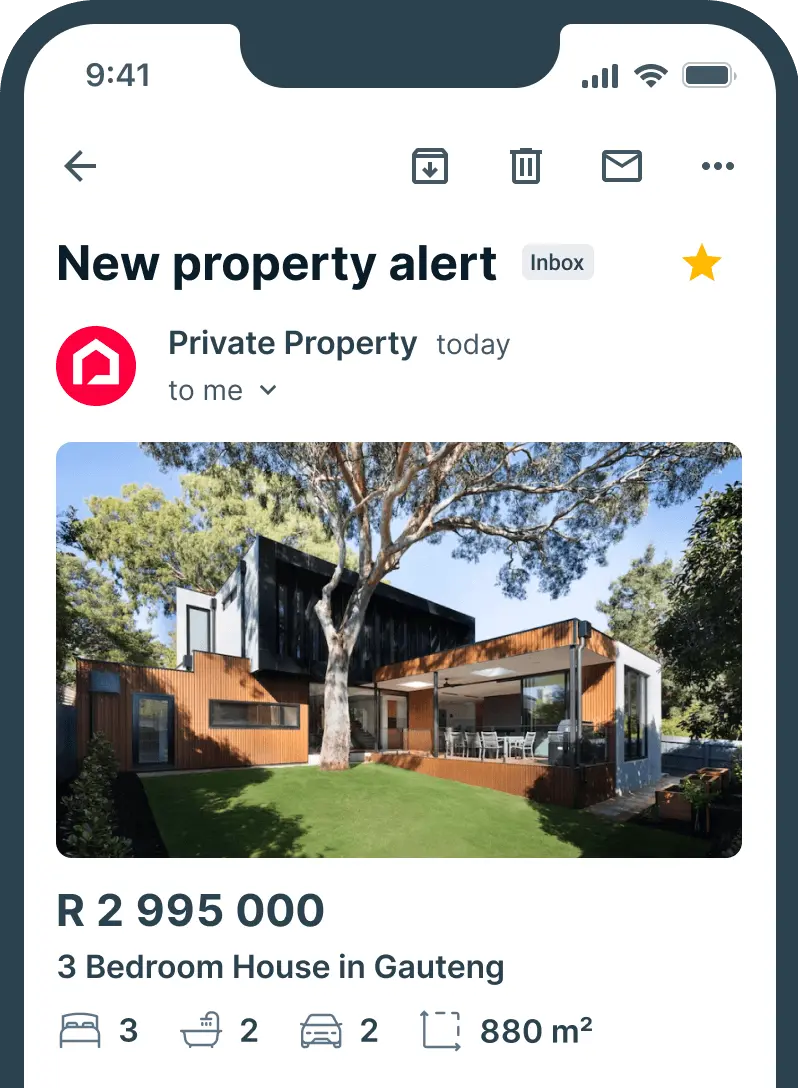

Living Streets also increase property values and attract property developers who rejuvenate dilapidated buildings, morphing them into attractive apartments for singles and small families, with pull cards like penthouses offering high-end fittings. Even property that would be considered unlivable in its current state could attract much higher prices than expected.

When the grime is removed, what is revealed is solid, even charming architecture that was intended to last for decades, if not centuries! For those architects, their buildings were tangible manifestations of how they saw generations of families interacting, bonding and uniting. In many ways, therefore, Living Streets honour past traditions by highlighting all the goodness of life and community.

"This is why when we create Living Streets, we are essentially nurturing a living organism," says Friedman, with Basschau adding that organic design ensures resilience against “shifts in the economy, society, and the environment.”

Standing testament to that resilience is the 30 years that Urban Lime has been reinventing buildings, districts, and neighbourhoods across two continents and has played a leading role in the transformation of Cape Town and Durban. Friedman cites Bree Street, Salt River and Church Square in Cape Town, and Florida Road and the Professional Quarter in Durban, which the organisation has helped to revitalise.

"We are currently launching a number of significant, catalytic projects across the country with the objective of repurposing neighbourhoods and buildings that are no longer relevant in the modern, technologically advanced, post-Covid environment,” confirms Friedman.

If we collectively - including private stakeholders working with local governments - take a more balanced, holistic approach to urban design, recover and preserve our city centres by embracing our growing multi-cultural society through the Living Street concept, the possibility exists to transform society and bring back, or stimulate our humanity.

Writer : Kerry Dimmer